As anyone who

has ever stepped into the poultry pavilion at any country show or fair will tell you, not

all chickens look the same.

And the most noticeable differences lie in the plumage... that is, the feathers. Not

just in the different colours and patterns either. There are other, more structural

differences. Now you might think that a feather is a feather is a feather, but when it

comes to chickens this just ain't so! So let's look at what makes up feathers and how

different genetic factors can alter the basics to give us all the wonderfully different

chickens we have today.

Firstly, let us look at what feathers actually do. They provide the bird with protection

from the elements, weather-proofing and maintaining body temperature. They allow the bird

to fly, therefore offering protection from predators and other danger and they provide the

means to attract the opposite sex. So how many feathers does a chicken actually have?

Studies have indicated each grown chicken carries in excess of 5000 feathers, with some

reports putting the number at closer to 7000, (though hard-feathered breeds such as Malay

Games which have large bare patches on their bodies, obviously carry less feathers than

say, a soft-feathered bird like a Cochin which carries profuse feathering). And of these

thousands of feathers, there is a wide variation of shapes and sizes, depending on the

functions they fulfill. Feathers which cover and help mould the shape of the bird are

called tetrices. Those which are softest and closest to the skin are plumule

feathers and those on the tail and wings which provide flight abilities are called quill

or flight feathers. There is one further type, known as filoplume, which are

hair-like and lie close to the skin. It is not known what function these provide.

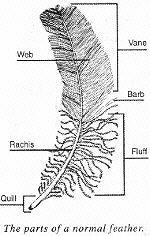

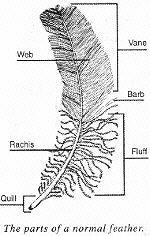

Most feathers consist of the following parts. The quill is

the hard stem which actually joins the feather to the bird's skin. This extends into the rachis

(or shaft). Extending out from the shaft close to the base is the fluff. Further

along the shaft comes the web which is the main surface of the feather. The edge of

the web is called the vane. The web consists of branch-like barbs which in

turn are lined with barbules and troughs. These interlock preventing air

from passing through, while still allowing the feather to remain flexible. It works in a

similar fashion to the fly zipper of your favourite jeans! The barbules and troughs are

easily separated creating breaks in the feather vane, the bird repairs these breaks by

running its beak along the separation and rejoining them just like a zipper. This is

partly what chickens do when they preen themselves. However, not all breeds of chickens

have these conventional feathers.

Most feathers consist of the following parts. The quill is

the hard stem which actually joins the feather to the bird's skin. This extends into the rachis

(or shaft). Extending out from the shaft close to the base is the fluff. Further

along the shaft comes the web which is the main surface of the feather. The edge of

the web is called the vane. The web consists of branch-like barbs which in

turn are lined with barbules and troughs. These interlock preventing air

from passing through, while still allowing the feather to remain flexible. It works in a

similar fashion to the fly zipper of your favourite jeans! The barbules and troughs are

easily separated creating breaks in the feather vane, the bird repairs these breaks by

running its beak along the separation and rejoining them just like a zipper. This is

partly what chickens do when they preen themselves. However, not all breeds of chickens

have these conventional feathers.

Silkies have a unique feather structure which gives them a fluffy

"hairy" appearance. Normal feather structure is caused by the 'H' gene, however

Silkies carry a recessive 'h' gene which is not present in other breeds of fowls. This

results in the barbules being elongated and lacking the conformation required to hook

together. It is this 'h' gene which gives the Silkie its strange woolly appearance.

Silkies have a unique feather structure which gives them a fluffy

"hairy" appearance. Normal feather structure is caused by the 'H' gene, however

Silkies carry a recessive 'h' gene which is not present in other breeds of fowls. This

results in the barbules being elongated and lacking the conformation required to hook

together. It is this 'h' gene which gives the Silkie its strange woolly appearance.

Another breed with distinctively different plumage is the

Frizzle. These birds have recurved feather shafts which makes the birds appear as if they

have been put backwards through a wind tunnel! The feathers all curve toward the head. It

is caused by an incompletely indominant gene 'F' and dependant on the influences of one of

three recessive modifying genes. This means there are three distinct types of frizzling.

The first of these gives extreme curling with narrow, weak feathers and a woolly

appearance. The second gives less extreme curling, longer feathers of stronger structure

(these are the exhibition type Frizzles). The last group display no frizzling at all yet

these are valuable as breeding stock, useful for improving feather length and quality.

Another breed with distinctively different plumage is the

Frizzle. These birds have recurved feather shafts which makes the birds appear as if they

have been put backwards through a wind tunnel! The feathers all curve toward the head. It

is caused by an incompletely indominant gene 'F' and dependant on the influences of one of

three recessive modifying genes. This means there are three distinct types of frizzling.

The first of these gives extreme curling with narrow, weak feathers and a woolly

appearance. The second gives less extreme curling, longer feathers of stronger structure

(these are the exhibition type Frizzles). The last group display no frizzling at all yet

these are valuable as breeding stock, useful for improving feather length and quality.

Next we have the Naked Necks. These birds have large, well

defined areas of skin where no feathers grow at all. The gene responsible for this

bare-necked appearance is 'Na', an incompletely dominant gene which also can give

sometimes up to 40% reduced plumage all over the bird. Some also have a goatee style

growth of feathers on the throat and rarely, fully feathered birds occur. Naked Necks also

have areas of bare skin under the wings, around the vent and along the tops of the thighs

and sides of the body.

Next we have the Naked Necks. These birds have large, well

defined areas of skin where no feathers grow at all. The gene responsible for this

bare-necked appearance is 'Na', an incompletely dominant gene which also can give

sometimes up to 40% reduced plumage all over the bird. Some also have a goatee style

growth of feathers on the throat and rarely, fully feathered birds occur. Naked Necks also

have areas of bare skin under the wings, around the vent and along the tops of the thighs

and sides of the body.

Finally, we have the long-tailed fowls of Japan. The Onagadori

(Phoenix or Yokohama in the west) carries a gene which prevents the male birds moulting

the tail feathers. These can grow to incredible lengths of 30 feet or longer and are

highly prized in their native Japan, though great care in raising such birds is needed as

it takes some 10 years to attain such plumage. The females have normal length tails. For

some reason, birds reared in the west never attain the spectacular length of feather as

those found in Japan.

Finally, we have the long-tailed fowls of Japan. The Onagadori

(Phoenix or Yokohama in the west) carries a gene which prevents the male birds moulting

the tail feathers. These can grow to incredible lengths of 30 feet or longer and are

highly prized in their native Japan, though great care in raising such birds is needed as

it takes some 10 years to attain such plumage. The females have normal length tails. For

some reason, birds reared in the west never attain the spectacular length of feather as

those found in Japan.

Most feathers consist of the following parts. The quill is

the hard stem which actually joins the feather to the bird's skin. This extends into the rachis

(or shaft). Extending out from the shaft close to the base is the fluff. Further

along the shaft comes the web which is the main surface of the feather. The edge of

the web is called the vane. The web consists of branch-like barbs which in

turn are lined with barbules and troughs. These interlock preventing air

from passing through, while still allowing the feather to remain flexible. It works in a

similar fashion to the fly zipper of your favourite jeans! The barbules and troughs are

easily separated creating breaks in the feather vane, the bird repairs these breaks by

running its beak along the separation and rejoining them just like a zipper. This is

partly what chickens do when they preen themselves. However, not all breeds of chickens

have these conventional feathers.

Most feathers consist of the following parts. The quill is

the hard stem which actually joins the feather to the bird's skin. This extends into the rachis

(or shaft). Extending out from the shaft close to the base is the fluff. Further

along the shaft comes the web which is the main surface of the feather. The edge of

the web is called the vane. The web consists of branch-like barbs which in

turn are lined with barbules and troughs. These interlock preventing air

from passing through, while still allowing the feather to remain flexible. It works in a

similar fashion to the fly zipper of your favourite jeans! The barbules and troughs are

easily separated creating breaks in the feather vane, the bird repairs these breaks by

running its beak along the separation and rejoining them just like a zipper. This is

partly what chickens do when they preen themselves. However, not all breeds of chickens

have these conventional feathers. Silkies have a unique feather structure which gives them a fluffy

"hairy" appearance. Normal feather structure is caused by the 'H' gene, however

Silkies carry a recessive 'h' gene which is not present in other breeds of fowls. This

results in the barbules being elongated and lacking the conformation required to hook

together. It is this 'h' gene which gives the Silkie its strange woolly appearance.

Silkies have a unique feather structure which gives them a fluffy

"hairy" appearance. Normal feather structure is caused by the 'H' gene, however

Silkies carry a recessive 'h' gene which is not present in other breeds of fowls. This

results in the barbules being elongated and lacking the conformation required to hook

together. It is this 'h' gene which gives the Silkie its strange woolly appearance. Another breed with distinctively different plumage is the

Frizzle. These birds have recurved feather shafts which makes the birds appear as if they

have been put backwards through a wind tunnel! The feathers all curve toward the head. It

is caused by an incompletely indominant gene 'F' and dependant on the influences of one of

three recessive modifying genes. This means there are three distinct types of frizzling.

The first of these gives extreme curling with narrow, weak feathers and a woolly

appearance. The second gives less extreme curling, longer feathers of stronger structure

(these are the exhibition type Frizzles). The last group display no frizzling at all yet

these are valuable as breeding stock, useful for improving feather length and quality.

Another breed with distinctively different plumage is the

Frizzle. These birds have recurved feather shafts which makes the birds appear as if they

have been put backwards through a wind tunnel! The feathers all curve toward the head. It

is caused by an incompletely indominant gene 'F' and dependant on the influences of one of

three recessive modifying genes. This means there are three distinct types of frizzling.

The first of these gives extreme curling with narrow, weak feathers and a woolly

appearance. The second gives less extreme curling, longer feathers of stronger structure

(these are the exhibition type Frizzles). The last group display no frizzling at all yet

these are valuable as breeding stock, useful for improving feather length and quality. Next we have the Naked Necks. These birds have large, well

defined areas of skin where no feathers grow at all. The gene responsible for this

bare-necked appearance is 'Na', an incompletely dominant gene which also can give

sometimes up to 40% reduced plumage all over the bird. Some also have a goatee style

growth of feathers on the throat and rarely, fully feathered birds occur. Naked Necks also

have areas of bare skin under the wings, around the vent and along the tops of the thighs

and sides of the body.

Next we have the Naked Necks. These birds have large, well

defined areas of skin where no feathers grow at all. The gene responsible for this

bare-necked appearance is 'Na', an incompletely dominant gene which also can give

sometimes up to 40% reduced plumage all over the bird. Some also have a goatee style

growth of feathers on the throat and rarely, fully feathered birds occur. Naked Necks also

have areas of bare skin under the wings, around the vent and along the tops of the thighs

and sides of the body. Finally, we have the long-tailed fowls of Japan. The Onagadori

(Phoenix or Yokohama in the west) carries a gene which prevents the male birds moulting

the tail feathers. These can grow to incredible lengths of 30 feet or longer and are

highly prized in their native Japan, though great care in raising such birds is needed as

it takes some 10 years to attain such plumage. The females have normal length tails. For

some reason, birds reared in the west never attain the spectacular length of feather as

those found in Japan.

Finally, we have the long-tailed fowls of Japan. The Onagadori

(Phoenix or Yokohama in the west) carries a gene which prevents the male birds moulting

the tail feathers. These can grow to incredible lengths of 30 feet or longer and are

highly prized in their native Japan, though great care in raising such birds is needed as

it takes some 10 years to attain such plumage. The females have normal length tails. For

some reason, birds reared in the west never attain the spectacular length of feather as

those found in Japan.